Whay carbon removal actually is, why it matters, and how ESG managers should think about it

Carbon removal has moved from a niche scientific concept to a board-level topic almost overnight. If you work with ESG, sustainability, or climate reporting, you have probably noticed the shift. Companies are no longer only asked how fast they reduce emissions. They are increasingly asked what they plan to do about the emissions that remain. That is where carbon removal comes in.

This article explains what carbon removal actually is, why it matters, and how ESG managers should think about it without getting lost in technical jargon or abstract theory.

Carbon removal means taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and storing it for a long time. Not avoided. Not delayed. Removed.

That distinction matters more than most people think. Emissions reductions slow the flow of CO₂ into the atmosphere. Carbon removal reduces the stock that is already there.

In practice, carbon removal includes approaches like direct air capture with geological storage, biomass-based solutions with permanent storage, and certain mineral-based pathways. What they all share is the same goal: move CO₂ from air to stable storage for decades, centuries, or longer.

For ESG managers, the key point is this. Carbon removal addresses residual emissions. These are the emissions a company cannot fully eliminate even after aggressive reduction efforts. Think hard-to-abate sectors, legacy supply chains, or structural emissions that do not disappear with efficiency gains.

Most corporate climate strategies start with reductions. That is sensible. Energy efficiency, renewable power, supply chain engagement. These actions should always come first.

But here is the uncomfortable truth. Even the most ambitious net-zero pathways leave residual emissions. Aviation, cement, chemicals, shipping, and agriculture all face physical and economic limits to how fast they can fully decarbonise.

This is not a corporate opinion. It is a scientific one.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, limiting global warming to 1.5°C or even well below 2°C requires both deep emissions reductions and large-scale carbon dioxide removal. In the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, most mitigation pathways consistent with 1.5°C rely on removing roughly 5 to 10 gigatons of CO₂ per year globally by mid-century, alongside steep emissions cuts. Without carbon removal at this scale, stabilising the climate becomes significantly more difficult.

That is not a future optional add-on. It is a structural requirement of the climate system.

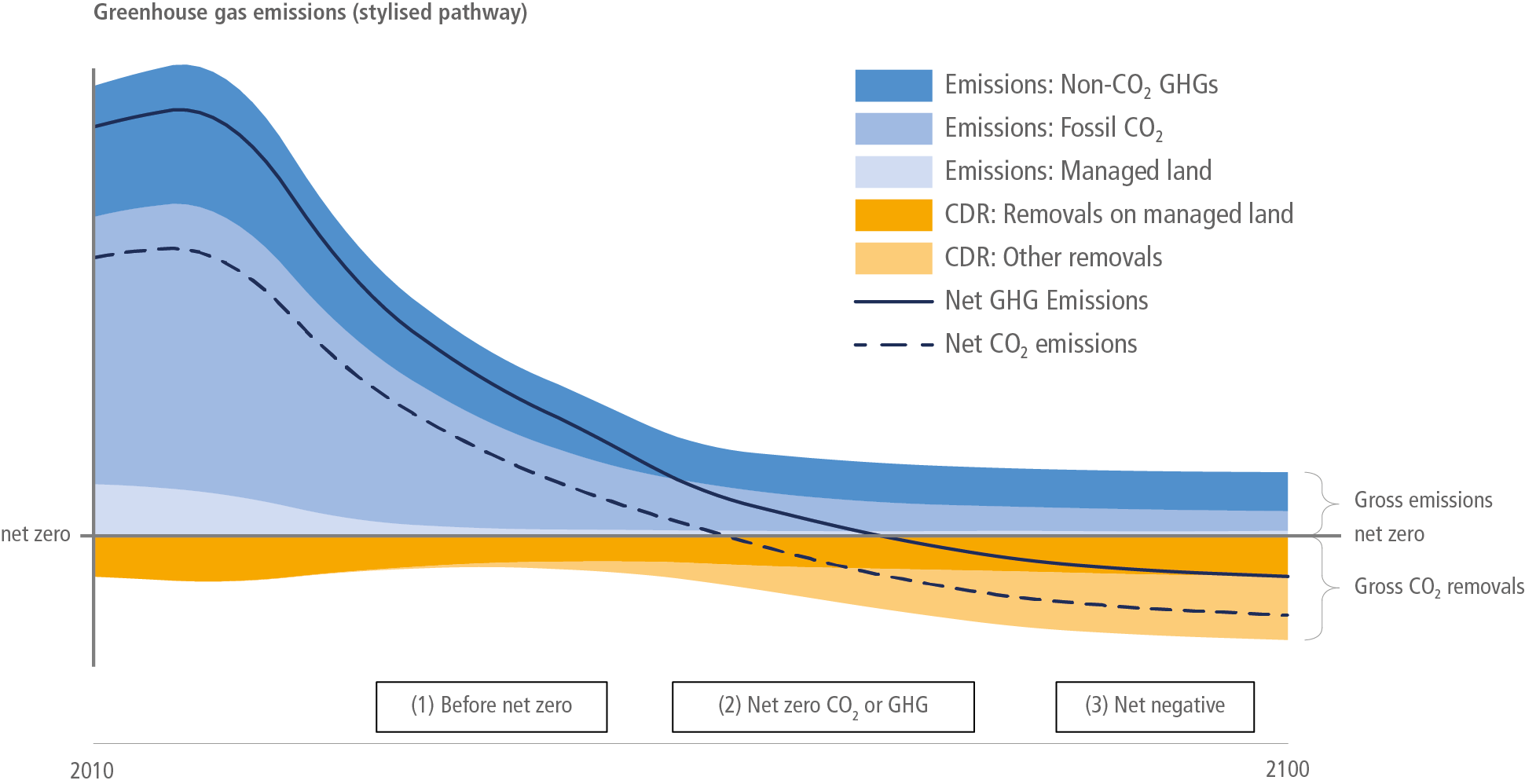

The figure illustrates a stylised global greenhouse gas pathway consistent with climate stabilisation scenarios assessed by the IPCC.

Even as gross emissions decline sharply, they do not disappear entirely. Fossil CO₂, non-CO₂ greenhouse gases, and emissions from managed land persist at lower but meaningful levels. These residual emissions remain even under highly ambitious mitigation pathways.

To balance them, carbon dioxide removal must scale. This is shown by the areas below the net-zero line. As emissions approach net zero, removals increase to counterbalance what cannot be eliminated. Beyond net zero, removals grow further to achieve net-negative emissions, reducing the overall concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere over time.

For ESG managers, the implication is clear. Net zero is not achieved through reductions alone. It is achieved by combining deep reductions with durable, verifiable carbon removal.

The pathway also highlights a timing challenge. Carbon removal capacity does not appear overnight. It must be developed gradually, supported by long-term planning and credible demand signals.

Source: IPCC (2022), Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group III.

From an ESG perspective, carbon removal plays a very specific role. It is not a substitute for reductions. It is a complement.

Well-designed strategies follow a clear logic.

This hierarchy is increasingly reflected in emerging standards, investor expectations, and stakeholder scrutiny. Companies that try to shortcut this logic risk reputational damage. ESG managers know this pressure well.

Carbon removal, when used correctly, strengthens credibility. It signals that a company understands the limits of reductions and takes responsibility for its climate impact beyond easy wins.

One of the biggest sources of confusion in the market is the word credit. It covers very different realities.

Many traditional carbon credits are based on avoided emissions. For example, funding a project that claims emissions would have been higher without intervention. These approaches can play a role in transition finance, but they do not remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Carbon removal credits are fundamentally different. They represent a verified quantity of CO₂ that has been physically removed and stored.

For ESG managers, this distinction matters because stakeholders are learning fast. Procurement teams, auditors, NGOs, and regulators increasingly ask not just how many credits were purchased, but what those credits actually represent.

Choosing carbon removal is less about volume and more about integrity.

There is a natural temptation to wait. Many companies plan to address residual emissions later, closer to their net-zero target year.

That strategy carries risk.

Carbon removal capacity is limited today. Scaling it takes time, infrastructure, and capital. As more companies commit to science-based targets, demand for high-quality removal will rise faster than supply.

Early engagement allows companies to learn, shape procurement strategies, and avoid future bottlenecks. It also spreads cost over time instead of concentrating it in the final years before a target deadline.

From a governance perspective, this is a familiar pattern. Early planning usually costs less than late compliance.

Carbon removal should not sit in a footnote of the climate plan. It touches multiple ESG dimensions.

For ESG managers reporting to boards or investors, this framing matters. Carbon removal is not a feel-good purchase. It is part of managing long-term climate risk.

If you are responsible for ESG or sustainability strategy, a few practical questions help cut through the noise.

You do not need all the answers on day one. But asking the questions early changes the quality of the strategy.

Carbon removal is no longer theoretical. It is becoming a necessary component of credible corporate climate action.

For ESG managers, the challenge is not whether carbon removal matters. The challenge is how to integrate it responsibly, transparently, and in a way that strengthens trust.

Handled well, carbon removal does not weaken climate ambition. It completes it.

For many companies, the hardest part is not deciding that carbon removal belongs in the strategy. It is finding a practical way to engage with the market that is structured, credible, and defensible under scrutiny.

High-quality carbon removal projects often look more like infrastructure contracts than simple credit purchases. They involve long development timelines, evolving MRV requirements, and commercial terms that benefit from careful structuring.

Pure Carbon Partners supports ESG teams and corporate buyers in developing offtake agreements with investment-grade carbon dioxide removal projects, focusing on durability, verification, and long-term credibility. The goal is not to buy “something that sounds good”. The goal is to secure access to real removals that stand up to investor, auditor, and stakeholder expectations.

If carbon removal is part of your climate strategy, a short conversation early in the process can be surprisingly useful. Not a sales pitch. Just a structured discussion about residual emissions, timing, and what quality should mean for your organisation.

If that sounds relevant, let’s talk.

.svg)